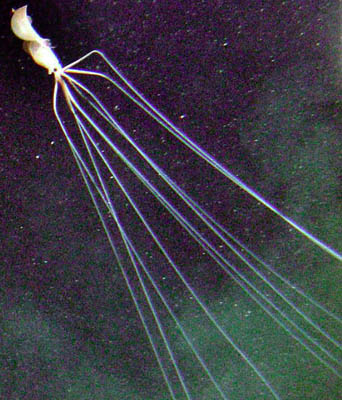

Stygiomedusa gigantea, commonly known as the giant phantom jelly, is the only species in the monotypic genus of deep sea jellyfish, Stygiomedusa. It is in the Ulmaridae family. With only around 110 sightings in 110 years, it is a jellyfish that is rarely seen, but believed to be widespread throughout the world, with the exception of the Arctic Ocean. The bell of this deep-sea denizen is more than one meter (3.3 feet) across and trails four ribbon-like oral (or mouth) arms that can grow to more than 10 meters (33 feet) in length.

The giant phantom jelly occurs all around the world with the exception of the Arctic Ocean. They are typically found 61°N–75°S and 135°W–153°E. In areas of high latitude in the Southern ocean, the depth at which the species may be found are at the mesopelagic and epipelagic levels.

Known to be one of the largest invertebrate predators in the deep sea, the giant phantom jellyfish's typical prey consists of plankton and small fish. The S. gigantea tends to be more dominant in locations with a low productivity system, which in turn deters other predatory organisms, like fish, to high productivity systems (coastal, upwelling zones). However, the jellyfish remains an important predator for the deep sea, often competing with squids and whales.

Evidence has been collected to support the first-ever documented symbiotic relationship for an ophidiiform fish, Thalassobathia pelagica. Scientists have observed that the large umbrella-shaped bell of S. gigantea provides food and shelter for T. pelagica, while the fish aids the giant phantom jelly by removing parasites. The S. gigantea's jelly providing shelter for T. pelagica is essential for the fish, considering the lack of shelter resources at such extreme ocean depths. Studies to further support this symbiotic relationship have shown that the two species reassociate with one another even if separated. It was inferred that T. pelagica is able to find its way back to the giant phantom jelly due to neuromasts that increase the sensitivity of low-frequency water movements which the bell of the jellyfish emits.

Instead of alternating between their medusa and polyp stages like most jellyfish, the giant phantom jelly covers their young in their huge bell. As a result, they "give birth" to young that are already at their medusa stage. It is inferred that reproduction of S. gigantea is continuous with one parent estimated to produce fifty to one hundred medusa.

Good another step forward for humanity